The Backstory

Among the strangest aspects of my sudden departure from Snag is that, just a week before, we launched one of the greatest endeavors of my professional life–a top-to-bottom rebrand of the company.

Even before joining Snagajob in January 2017, the possibility of a rebrand was discussed with me. The company had acquired PeopleMatter, an enterprise software company, and had launched a pilot on-demand service, HUSL, and all these brands lead to confusion both in the market and internally. The name “Snagajob” was much too specific to the company’s job board past, had no relevance to employers, and, frankly, was a bit sophomoric and could be hard to take seriously.

So, from the day I started, January 2, 2017, I was the lead executive on rectifying this brand challenge, partnered with Bridget Walsh, our director of communication design. There is some irony to me leading brand, as I’m not really a brand guy. I’m a research-strategy-information architecture-interaction design guy. I am skeptical, even dismissive, of much of the discussion around brand1Never forget, branding is the application of a red hot iron to the hide of livestock..

That said, my first design industry job (1996-1998) was at Studio Archetype, a design firm that grew out of a specialization in identity and communication design to become a pioneer in CD-ROM and web design. And so while skeptical, I appreciate the wizardry of truly gifted brand professionals.

Thankfully, I inherited a big-enough budget to bring on external help to guide us through this. An early realization was that there were two projects here–clarify our brand strategy, and then, based on that, develop a new visual identity.

Choosing a strategy partner

We interviewed a few potential partners for the strategy work, and quickly settled on Great Monday, whose principle, Josh Levine, is an old friend of mine. We chose them because they were clearly smart and capable, pleasingly small (I think there’s only 3 full time staff), located in Oakland (as am I), and, importantly, Josh understood what we needed from him – not just a clever brand strategist, but a charismatic presence who could rally a room of people from across the company, who could speak with authority to our CEO and other executive team members, and who would do all the little things that it takes to see something through that is as fraught and anxiety-inducing as a total reconsideration of company’s brand.

Given that potential for anxiety, and given Snagajob’s size (mid-400s), age (17 years at this point), geographies (4 cities), and company philosophy (heavily mission-driven), Great Monday proposed a measured, thoughtful approach, designed to hand-hold us through every stage and maintain our confidence that we were on the right path. It also meant that it would take 4-5 months. Our executives wanted it sooner and pleaded with me to move faster, but I felt that in order for this to succeed, we needed to do it right – a rebrand isn’t something you get to iterate on in the market.

I won’t delve into every project detail. Suffice to say it included discovery, stakeholder and customer interviews, internal questionnaires, workshops, positioning and story development, brand architecture, and brand personality.

Oh and naming. That I do want to talk about. Before I do, it helps to set up a couple of things.

Brand Workshop Reveals Key Strategic Foundations

About a month and a half into the work, Great Monday hosted a workshop with 20 people pulled from all departments, and from all levels of seniority (though it was admittedly top-heavy).

They lead us through a series of activities, two of which proved crucial in defining our brand. In their discussions with internal stakeholders, the identified a few areas of tension. They placed opposing concepts on a simple single-line spectrum, and had us dot-vote where we thought we currently were, and where we should be. Two of these dominated our discussion:

- Were we a ‘tech’ company or a ‘people’ company?

- Do we lean more towards the worker or the employer?

The placement of the dots wasn’t nearly as important as the discussion it catalyzed. For the first, the passionate discussion made it clear that we were, and wanted to be perceived as, a ‘people’ company. In fact, we considered it ironic that in a jobs/work space that is so much about people, pretty much no competitor authentically embraced their humanism. The discussion around the second grew quite heated, as employers pay our bills, and many were adamant our brand should preference them. However, Great Monday had spoken to many employers, who expressed general apathy about our brand, saying that our value to them was our ability to appeal to workers. So we decided our brand would be ‘worker first.’

Brand Architecture Forces Focus

After the workshop, the next key decision we made was to settle on a brand architecture. At the time, Snagajob was a somewhat clumsy “house of brands.” The company was named Snagajob, and that name was used in our services that faced our jobseekers and workers. They had acquired PeopleMatter, an applicant-tracking SaaS offering, and kept that name as the brand facing employers. And then there was an innovation team that was developing an on-demand offering, which they branded as HUSL.

We had an opportunity to approach this thoughtfully. Should we keep this individual architecture where you have different brands under a corporate brand (think GM and Buick, Chevrolet, Cadillac); a monolithic architecture where there’s one brand to rule them all, with sub brands underneath (FedEx, and FedEx Ground, FedEx Express, FedEx Office), or a hybrid architecture that features a strong corporate brand, but gives room for subbrands that stand on their own (Marriott with Courtyard by Marriott, Residence Inn, J.W. Marriott, etc.). At our size (450 employees), and in our market (job marketplace, similar to Indeed and LinkedIn), it became quickly clear that monolithic was the way to go. No one else in our space had different names for the worker and employer facing services, and pretty much no marketplace business does. The strength of a marketplace is signaled by having one brand that hosts everybody.

If we’re going to have one name…

With the decision to be a monolithic brand, we then had to come to terms with the matter of the name. The easiest solution would be to call everything Snagajob. It’s how we’d been known for 17 years. The problem was that the name is distinctly worker-facing. Employers might not care, but it felt inappropriate to actively exclude them. But also, the company had evolved beyond jobs, with the most exciting opportunity being in on-demand, helping employers and workers make it easier to offer and pickup shifts. And while “Snagajob” may have felt dot-com appropriate when coined in 2000, by 2017 it came across as clunky and unprofessional.

I found out that, even before I joined the company, the idea of renaming it “Snag” had been floated. It mimicked Snapchat renaming themselves “Snap,” was brief and catchy, and maintained some brand equity while allowing for offerings beyond jobs. However, the word “snag” has primarily negative connotations (hitting a snag, a snag in sweater). Unsure quite how to proceed, we engaged in a naming exercise with Great Monday.

Naming is a bit of a black art. We fed them a bunch of brand names we liked and didn’t like, and the reasons why. We also had our brand positioning and personality characteristics (more on those later). After many days of what I assume was playing with morphemes, paging through dictionaries and thesauruses, and long soaks in the bathtub, they presented us about 20 names to consider, and another 100-plus that had also come up. We went through a few rounds of throwing things away, coming up with new stuff, and eventually had a selection of 3 names that we liked.

(No, I’m not going to share them with you. Maybe over beers.)

The problem is, we couldn’t agree on them. Of the 5 or 6 people on the ‘core team’ for the brand, there was no consensus. And our executive sponsors also didn’t align. Our CEO pointed out that what we think doesn’t matter nearly as much as what our jobseekers and workers thought, so why don’t we ask them? So we set up one of the quickest bits of research I’ve overseen in my career, talking individually to 12 jobseekers (NO FOCUS GROUPS. EVER.) across the United States about the three names we were considering. Oh, and we threw “Snag” in there as well to see how it compared. We asked them their impressions of the different names, and then we had them rate the names against each of our brand personality traits, as we wanted to make sure that the name spoke to how we wanted to be perceived.

Coming out of the research, jobseekers exhibited a variety of preferences, with no one clear “winner.” But, to our surprise, the name that scored strongest was…Snag. After all that work, it turned out the right name was there the whole time. There were no regrets about the process – we needed to go through that rigamarole to have confidence that Snag could, in fact, work for us.

If you were a tree, what kind of tree would you be?

Going all the way back to the brand workshop, there was another activity that proved key to our brand strategy. And that was having each of us propose a spokesperson for the brand, someone, out in the world, who represents what we felt our brand stood for. People came up with all kinds of answers. I don’t remember them all, but some were America Ferrara, Zendaya, Barack Obama.

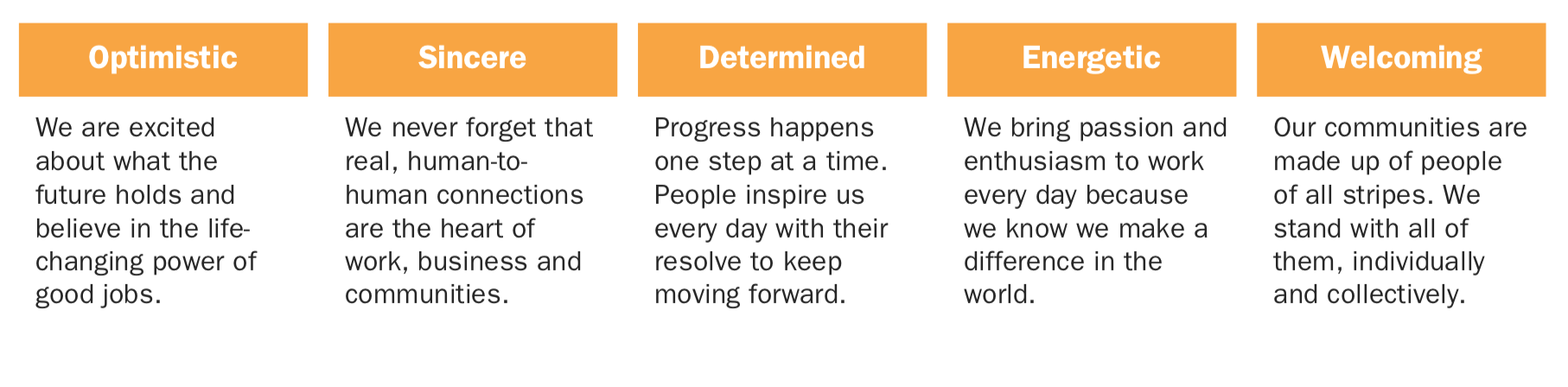

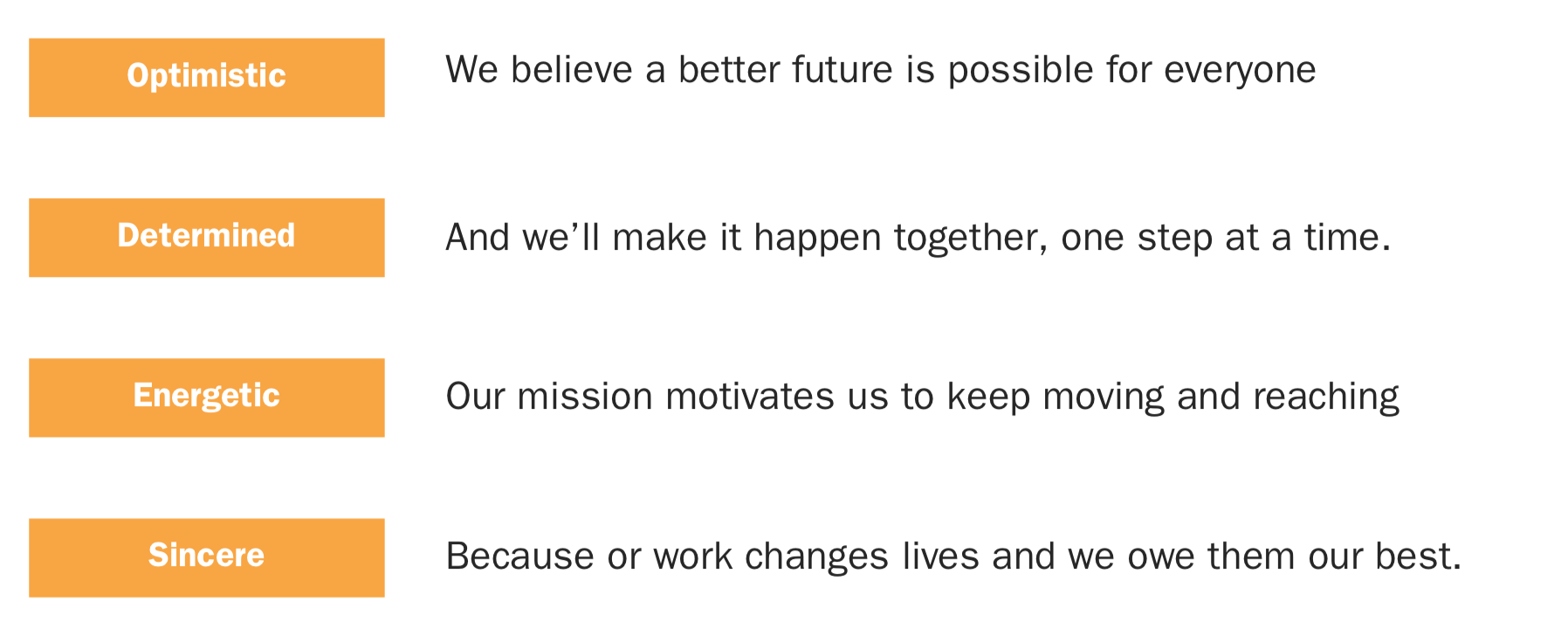

For each spokesperson we listed 3 to 4 personality traits that explained why they were a good representative. Across the 20 or so spokespeople, we had 70-some adjectives emerge. After some sorting and categorizing, we arrived at the following groups:

We knew this was too many. And some, like “Human” and “Genuine” have become cliches; even if they are true for you, they’re no longer interesting as brand characteristics, as too many companies claim them. Key to successful brand traits is that they’re a) authentic and b) ownable. To be ownable, it means that no other competitor could claim them. (You also want to avoid traits that are really just table stakes for being in business, like “trustworthy.”) With that mindset, we got it down to:

However, we felt 5 was more than could be readily remembered, so we got out our scalpel, and trimmed it to:

I love these traits. They strongly resonate with Snag’s internal culture. They’re humanistic. They’re candid — “determined” recognizes the toil it takes to succeed. They’re unexpected – “sincere” is surprisingly sentimental for a company (we almost went with “heartfelt” but thought that was a bit too much.)

With the brand strategy, architecture, new name, and new characteristics, we had a strong definition of our new brand. The next step was to figure out how to express that personality, which I will describe when I get around to writing part 2.

(For the sake of verbal expedience, I’m probably not spending enough time highlighting the individuals at Snag who made this all go. Along with Bridget, our core team featured Dane Schwartz, and then in the next concentric circle out was Jason Conrad and Megan Overton. None of this would have happened without the support of my boss, Jocelyn Mangan, or the encouragement of our CEO, Peter Harrison.)