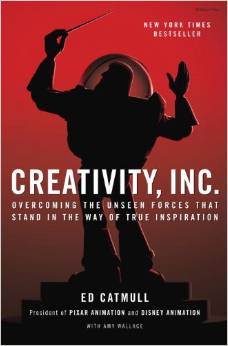

Creativity, Inc., by Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace, is an important work, not just as a business book, but as a piece of non-fiction. In it, Catmull shares his hard-won lessons on management from 40 years of work, the last 30 as President at Pixar.

Just given Pixar’s unparalleled success, Catmull would be worth listening to. However, he goes beyond expectations and shares his story with remarkable candor, humanity, wisdom, and humility.

In a book riddled with insights, the single most important is the overarching realization that any creative organization is a constantly evolving complex dynamic system. The book’s subtitle could have been Corralling Dynamism To Deliver Greatness.

This insight has a number of implications:

- practices that aim for certainty will curb creativity, and are fruitless anyway, because dynamism

- instead, embrace that dynamism, as it leads to unexpected awesomeness that couldn’t be predicted

- as dynamism is messy, develop practices that encourage discovery and recovery

- create feedback loops throughout the organization, so that this dynamism is continually tacking towards positive outcomes

- these feedback loops require candid communication throughout the entire organization, which means everyone needs to be comfortable sharing their thoughts and concerns, without fear of retribution

- like tending a productive garden, management and leadership’s work is never done, and just because something worked in the past doesn’t mean it will continue to do so

These implications scare the crap out of most senior leadership, who are under the notion of “you can’t manage what you can’t measure,” and who require certainty in the desire to be predictable. Catmull addresses this in one of my favorite passages:

“You can’t manage what you can’t measure†is a maxim that is taught and believed by many in both the business and education sectors. But in fact, the phrase is ridiculous—something said by people who are unaware of how much is hidden.

This is but a sliver of what the book offers. To do it justice, I’d pretty much have to rewrite the whole damn thing, so just go read it already.

There is one thing that the book punts on that I find crucial in any creative enterprise, and I’d love to ask Catmull why he didn’t address it directly. And that’s the matter of taste, of judgment, of knowing when something is great. Catmull takes it as a given that all ideas start crappy, but through iteration, interrogation, research, and refinement, they become great. But he doesn’t share when his team (particularly the Braintrust) knows when to be satisfied that something is great enough and requires no further improvement.