A while back I posted about how product designs are getting too difficult, and how the greater the number of steps it takes for someone to set up a product, or to use a service, the less successful they will be. In it, I mentioned the Six Sigma concept of Rolled Throughput Yield: “the probability of being able to pass a unit of product or service through the entire process defect-free.”

Let’s say you have a website, and a registration process that takes four steps. Each step is pretty well-designed– 90% of users are able to complete each step. However, only 65% of people will actually make it through, because you’re losing people every step of the way (.9 x 4 = .65). The shows that often the best way to address the problem is not to improve the individual elements, but to remove elements altogether.

More recently, I wrote about how hard it is for organizations to produce well-designed products, because in order for a good design get out in the world, it has to run jump through a set of departmental hoops — be approved by the business owners, marketers, designers, engineers, manufacturers, etc. etc. At each step, the project can be stalled. Or so many people have to be pleased, products are “designed by committee” – not a recipe for innovation.

This struck me as a kind of organizational variant to Rolled Throughput Yield. Particularly because we’ve seen that the organizations that do support innovative design have smaller, multi-disciplinary teams, not departmental stovepipes. It also struck me that these are two sides of the same coin. The complexity of product from the first example is often a result of the complexity of organizations in the second — design by committee, or some form of serial design process, leads to products with too many discrete parts and interfaces, which are essentially invitations for something to go wrong.

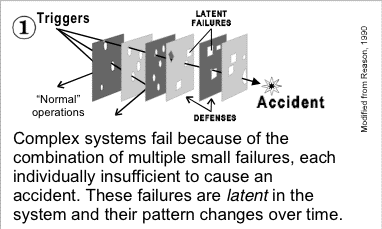

Separately, on a bit of a Googlewander, I came across David Woods, who, among other things, has written about “human error.”In reading some papers he wrote on the topic, I came across this diagram:

Taken from here (PDF), which is meant to be read in conjunction with this (PDF).

(I’ve been meaning to read more of David’s stuff for a while. I think the study of “human error” can be an insightful perspective for user-centered design.)

The challenge, of course, seems to be to manage complexity. Complexity seems to be a given. Is it? Is increasing complexity inevitable? Occasionally products emerge that massively reduce complexity (at least, complexity of use), and are popular — the original Palm (compared to earlier pen-based computing) and Google come to mind. Maybe the iPod (I don’t know how it stacks up to other music players from a complexity standpoint).

I don’t see the connection between the diagram & what you’re saying. The Woods / Cook papers discuss how accidents happen in complex systems & how to respond to them, but they don’t suggest reducing the complexity of those systems.

Peter,

if you’re looking for more on “human error” by David Woods, I suggest taking a look at the (inactive) coursemodule available here:

http://csel.eng.ohio-state.edu/productions/pexis/

trying again…

http://csel.eng.ohio-state.edu/productions/pexis/

You ask, ‘Is increasing complexity inevitable?’

Yep. It’s a natural/evolutionary law – simplicity tends towards complexity. then it optimises.

Google isn’t exempt. They just presented the ‘optimised’ version of a search engine, based on the complexity models of competitors and knowing what not to show.