Ostensibly a biography of Eadward Muybridge, whose motion studies fathered cinema, Rebecca Solnit’s River of Shadows is more an historic tapestry of early northern California. Solnit realizes that to chronicle Muybridge’s life is to weave together a variety of themes essential to the period (1850s to 1880s), beginning with the notion of “going west” to start afresh, to San Francisco’s Barbary Coast mores, linking the continent by rail, incipient environmentalism, and Native American relations.

.

Additionally, Solnit highlights how a single pursuit, Leland Stanford’s 1878 commission of Muybridge’s earliest motion studies, spawned two themes which would become essential to California in the following century. The most obvious theme is that of motion pictures, the defining industry of southern California. Second, and probably with more impact, Stanford’s patronage was perhaps the first serious pursuit of technological research in the young state, a precursor to the Silicon Valley which would grow around Stanford’s greatest legacy, the university that bears his name.

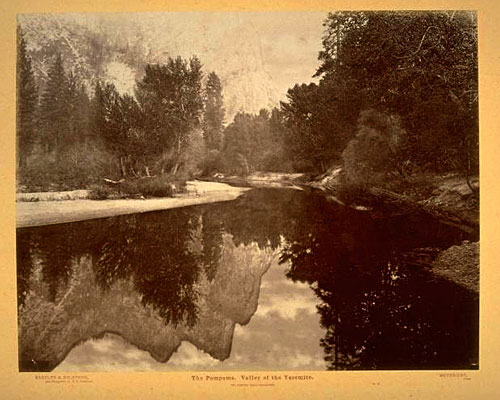

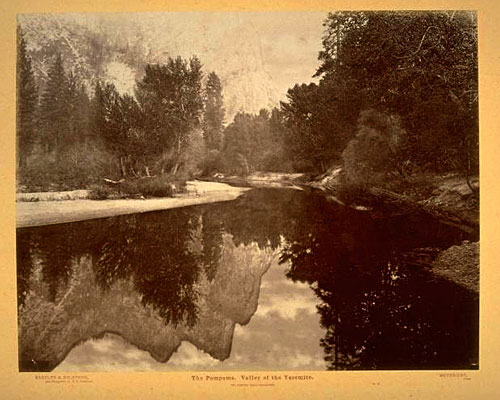

The Pompoms. Valley of the Yosemite. The Jumping Frogs Reflected. No. 13.

As a film history dilettante, I’d already been well aware of Muybridge’s motion work. What particularly intrigued me was learning of his earlier landscape efforts, including a set of mammoth (20″ x 24″) photos he took of Yosemite, including the one above. These pictures are available through the Bancroft Library and are definitely worth perusing.

Pigeon flying, from http://photo.ucr.edu/photographers/muybridge/index755.html

Perhaps Solnit’s most illuminating, and most frustrating, chapter is her last. Muybridge is dead, and she demonstrates the dominoes that subsequently toppled, leading to the motion picture industry and Silicon Valley. A valiant effort, it’s too much for just one chapter–there’s enough material for at least one book. Still, it’s a minor blemish in an otherwise captivating work that ought to resonate with many in California.

As a final note, it wasn’t until I read this book that I made the connection between Muybridge’s multiple camera set-up, each of which took a single shot so as to later simulate real motion, and the multiple camera set-up used to created the “Bullet Time” effect in The Matrix, each of which shoots film in order to create unreal slow motion.

Actually, this will be the final final note. One last impression I received from the book was how, not so long ago, “art” and “science” (or “technology”) weren’t really considered distinct discilpines. People just did what they did, and if it advanced art, great, and if it advanced science, great.

Woman pouring a bucket of water over another woman

1884-85, taken from here

Okay, I lied, this is the final note. Long time peterme readers know I used to write a lot about comics, spurred in large part by Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. It turns out, as demonstrated by the picture above, that Muybridge was a proto-photo-comics artist. His motion studies often contained simple narratives, meant to be ‘read’ when finally published.